To Join or Not to Join? Understanding the Succession Intentions of Next-generation Family Business Members

Dr Eric Clinton, NCFB Director

Dr Eric Clinton, Director NCFB

Family businesses are the dominant form of organisation worldwide. They constitute the majority of businesses in the Irish and Northern Irish economies, and like all businesses, they must future-proof themselves by adapting to ever-changing operating environments and consumer demands. Although the competitive landscape is increasingly challenging, Irish family businesses continue to integrate themselves competitively and innovatively in national and international markets.

We have witnessed their astonishing resilience in seeing off the global financial crisis, remaining steady in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic and adapting to the energy dilemma. Moreover, they contribute to significant philanthropic and social aims across the island of Ireland.

Family businesses are not footloose; they are embedded in local communities, employ local people, source local produce and service local markets. As a society we can learn a lot from Germany, where the economic engine of the economy is fuelled by family businesses in the Mittelstand region and government policy encourages ownership transition while actively promoting entrepreneurship across generations.

Key to family businesses’ longevity and transgenerational survival is an effective succession process; yet, when family and work dynamics combine, family businesses face distinct succession-led challenges: leadership planning, nurturing family talent, family governance, and the integration of non-family executives. Choosing the most qualified successor is an essential part of handling this complex uncertainty, but global studies suggest that succession intentions among next-generation members are low, creating a ‘succession crisis’.

Following a conversation among colleagues in Dublin City University’s National Centre for Family Business (NCFB) and at Ulster University, University College Cork and the University of Limerick, a partnership was formed to conduct an all-island study to test the factual basis that there is a succession crisis across the island of Ireland.

We found that succession aspirations are healthy across the island of Ireland, and the shaping of next-generation intentions regarding educational choices, sustainability, emotional well-being and socio-emotional wealth has a vital role to play in the realisation of these aspirations.

“I would like to thank all the next-generation members who participated in our study, especially those who volunteered their family business profiles for this report. Thank you also to our sponsor, AIB . We hope the evidence-based and theory-driven recommendations in this report will provide practical steps and tools for family businesses managing succession planning for years to come."

Professor Dominic Elliott, Dean DCU Business School

Professor Dominic Elliott, Dean DCU Business School

Looking towards 2030 and beyond, Irish businesses must address the interlocking challenges of transitioning to a low-carbon economy, embracing digital transformation, and absorbing external shocks and higher operational costs resulting from global insecurity.

Given their continued prominence in the Irish economy, family businesses will have a leading economic role to play in remaining strong when faced with the financial uncertainties and unexpected shocks that these trends will bring.

The NCFB led this timely all-island university partnership, recruiting almost 400 next-generation family business university students to give the pursuit of succession a contemporary voice. This report reveals the drivers and inhibitors of next-generation succession intentions. This is connected to sustainability in a climate crisis context, and sheds new light on how these intentions interact with attachment and commitment, trust, well-being and family businesses’ socio-emotional wealth. More than half of the respondents were young women presenting a unique opportunity to understand more about the generational shift for young women in purpose and influence. As well as learning about the forces shaping next-generation succession intentions, the findings provide unique insight into the new phenomenon of transgenerational entrepreneurship – a key area of strength for the Dublin City University (DCU) Business School.

It has been our privilege to work with these families and students. The cutting-edge research produced will deliver key insights for higher-education institutions and businesses through tailored educational programmes, and co-create actionable insights that will sustain and develop Irish family businesses into the future. Finally, I want to thank the students sincerely for their commitment and enthusiasm in sharing their aspirations, and to wish them continued success in their future family business endeavours.

John Brennan, AIB

Why AIB supports the NCFB’s research and engagement efforts

In the dynamic landscape of family businesses, where tradition and innovation converge, the succession intentions of the next generation are pivotal to the sustainability and preservation of these enterprises. This research endeavours to unravel the intricate tapestry of succession intentions within these enterprises. It’s a topic of real importance to AIB and our customers as we endeavour to support them in planning for a sustainable future.

AIB has been backing SMEs for decades. Fostering a deep understanding of the challenges faced by family businesses is of critical importance to us, and we believe supporting academic endeavours such as this one is integral to bridging the gap between theory and practice.

AIB

The contribution and participation of the next generation will be crucial to the success and growth of family businesses which underpin the long-term resilience of our economy.

I extend my gratitude to the authors for their dedication in conducting this all-island study to explore this crucial aspect of family businesses, to the students that participated in the survey and interviews, and I am confident that the insights presented will be a valuable resource for academics, practitioners, and our SME community alike.

Temple family of Magee 1866, 5th-generation family business

Family businesses are the dominant form of organisation worldwide. They are known for exercising the dynastic will to build strong businesses and global leading brands, guided by both family and business goals. Indeed research shows that family businesses regularly out-perform their their non-family counterparts across a variety of key performance metrics, including turnover, innovation and international development.1

In the Republic of Ireland, family businesses form the economic and social bedrock of our communities, representing over 64% of all firms, and contributing to almost fifty-percent of GDP.2

1. Credit Suisse. (2018). The CS Family 1000 in 2018. Credit Suisse Group. www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/about-us/research/publications/the-cs-family-1000-in-2018.pdf

2 O’Gorman, C., & Farrelly, K. (2020). Irish Family Business by Numbers. National Centre for Family Business, Dublin City University.

It is estimated that if family businesses were a global national economy, they would be the third largest of the world’s ‘trillion dollar economies’, after the USA and China.3,4

Across the globe, family businesses have made a significant contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) and economic development, including in India (79%), Spain (70%), Mexico (70%), Italy (68%), the UK (67%), Portugal (67%), Canada (60%), the USA (54%), China (51%) and Germany (49%).5

3 Clinton, E., & Brophy, M. (2020). Family Businesses - Bedrock of the Economy. National Centre for Family Business.

4 Neufeld, D. (2023, December 20). The Influence of Family-Owned Businesses, by Share of GDP. Visual Capitalist.

5 Robertsson, H. (2023). 2023 Family Business Index.

Despite the prominence and contributions of family businesses worldwide, a succession crisis has emerged. This crisis is partly due to improved labour markets presenting would-be successors with more choice. Global studies suggest that succession intentions among next-generation family business members are low. Research has demonstrated trends that few next-generation students attending university are intent on joining the family business, and less than 5% plan to become a successor directly after their studies, or even 5 years thereafter.6 When it comes to family business survival, on average, only 30% of family businesses make it to the second generation, 10–

15% make it to the third generation and a mere 3–5% make it to the fourth generation.7

Indeed, many countries around the world have colloquial sayings for the survival of family businesses across generations, such as ‘rags to riches back to rags in three generations’ or ‘shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations’.

6 Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Van Rij, M. (2017). Coming home or breaking free? A closer look at the succession intentions of next-generation family business members. Family Business Centre of Excellence.

7 Ward, J. (2004). Perpetuating the Family Business: 50 Lessons Learned from Long-Lasting, Successful Families in Business. Palgrave Macmillan London.

Succession planning is critical to future-proofing a business. A central tenet to family business longevity and survival across generations is an effective succession process, which is heavily dependent on next-generation succession intentions: the desire of members of the next generation to pursue a leadership role in the family business. Next-generation succession intentions often only materialise when next-generation members are both willing and able to contribute to business continuity.

Failure to plan for the medium and long term in this way ultimately damages the viability of the family business for future generations. Yet, the family business field has accumulated little insight into what drives or suppresses succession intentions.8

Much of what we know about succession in family businesses is focused on the incumbent generation and what they wish to do about

passing the business on to their children. Factors such as efficient tax structures, ownership transition and family business governance alone do not explain succession intentions (or the lack thereof). Relationship dynamics such as attachment versus commitment, education and life choices, parental support, trust, well-being, and the promise of associated social status and reputation could all impact on succession intentions.9

In short, there is an uneven distribution in our understanding of next generation members and their aspirations, challenges and anxieties about joining the family business. As we seek to build resilient family businesses in our communities across the island of Ireland, we have reached a pivotal moment in terms of gaining an understanding of the myriad of factors that constitute the succession challenges facing our future leaders.

Some of the questions next-generation members often ask include:

- How will I gain respect within the organisation?

- Is this a job for life?

- Do people think I got the position just because my family owns the business?

- Will this role offer me a sense of purpose?

- When can I discuss ownership with my parents?

- How can I move out of the shadow of my father/mother?

- How can I work with cousins I barely know?

- How can I work with senior staff who are my parents’ age?

- How can I get the shareholders (my family) to support me?

- Are my qualifications enough?

- What about entrepreneurship outside the business?

- How can I change the board of directors?

- Should I work outside the business before joining?

- How do I raise social entrepreneurship with the family?

8 Gimenez-Jimenez, D., Edelman, L. F., Minola, T., Calabrò, A., & Cassia, L. (2021). An intergeneration solidarity perspective on succession intentions in family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 45(4), 740-766.

9 For example, see Lyons, R., Ahmed, F. U., Clinton, E., O’Gorman, C., & Gillanders, R. (2023). The impact of parental emotional support on the succession intentions of next-generation family business members. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 1-19.

Employing nationwide surveys and interviews with higher-education students from a family business background, this project uncovered ample evidence that the succession crisis may not be so stark for the island of Ireland. Although only one-third of the next-generation family business respondents who participated had a succession plan in place, the emerging pattern of succession aspirations from our next-generation respondents is healthy. Almost half have seriously thought about taking over their family’s business one day, especially male potential successors, whose aspiration is twice that of women. Four out of five respondents have worked in their family’s business and agree that they experience a high level of psychological ownership, but not actual financial ownership, of the business. Most have exercised their right to choose their formal higher education pathway regardless of how formative it is to becoming a successor. They believe that the level of interest and experience in the business, rather than birth order, will decide who will be the successor.

Most respondents report positive well-being and positive emotions and feelings with regard to the family business, as well as possessing a strong sense of attachment and aspiring to contribute to the continued success of the business. Most perceive their family’s business as heeding good ethical understanding and practices.

Moreover, they agree that the family should participate in the community and would benefit from the social relationships developed. The aspiration of contributing to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of ‘decent work and economic growth’ ranked highest in importance among the three SDGs evaluated as part of our study. Finally, access to finance, availability of talent, and obstacles to effective succession were judged to be the main challenges facing family business succession.

Overall, we found that succession aspirations are healthy across the island of Ireland, and educational choices, sustainability, emotional

well-being and socio-emotional wealth each have a vital role to play in the shaping of next-generation. With its rich and novel set of findings, this report will better inform Irish Government and European Union policy positions on family business succession.

Has the next generation thought of taking over their family’s business?

Forty-eight percent have seriously thought about taking over their family’s business, and 40% have strong intentions to become a successor in their family’s business one day, especially male potential successors, whose intention is twice that of women.

How does the next generation perceive their ownership role in the family’s business?

Eighty-five percent do not hold a financial ownership stake in their family’s business, with only 15% reporting the possession of ownership stock. Nonetheless, 39% of next-generation members reported feeling a very high degree of psychological ownership for the business.

Is the next generation emotionally attached to their family’s business?

Most have a close sense of attachment to their family business, and have strong positive feelings for it. However, 33% of respondents had negative or neutral feelings of attachment towards their family’s business.

Is the choice of education connected to the next generation’s career in the family business?

Thirty-three percent of respondents agree that their formal education is connected to their career path in the family business, with a notable leaning towards business-related subjects.

Does the next generation prioritise embedding sustainability into their family’s business?

The next generation ranked contributing to decent work and economic growth as the most important SDG should they become a successor in their family’s business.

Is prioritising sustainability related to the next generation’s succession intentions?

Overall succession intentions are aligned with SDGs aspiration. The next generation’s intention to become a family business successor is in part related to making a positive impact on the environment.

What non-financial benefits do the next generation derive from being part of their family’s business?

Seventy-three percent agree that their family business is recognised for positively contributing to the local community.

Capturing an all-Ireland family business succession response

Total respondents: 375

Gender: 175 men, 198 women, 1 other

Average age: 22 years

University

- Dublin City University: 47%

- University College Cork: 8%

- University of Limerick: 12.5%

- Ulster University: 30.5%

- Other 2%

Year family business founded

- Pre 1800s: 0.5%

- 1800s: 3%

- 1900-1950: 6%

- 1951-1999: 41%

- 2000s: 49%

- Unknown: 0.5%

Family business size

- Micro <10: 47%

- SME 10-49: 36%

- Medium 50-249: 11.5%

- Large 250+: 5%

- Unknown: 0.5%

Sector breakdown

- Agriculture (Family Farm) or Agriculture Other: 17%

- Communications/ Information: 2%

- Construction/ Property: 13%

- Energy: 0.5%

- Entertainment/ Arts: 0.5%

- Finance/ Insurance: 4%

- Food: 8%

- Forestry/ Fishing: 0.5%

- Hospitality / Tourism: 8%

- Non-profit: 0.5%

- Pharma: 1%

- Professional, Administrative and Support Services: 3%

- Public Administration, Education and Health: 3%

- Retail: 11.5%

- Manufacturing: 5%

- Technology: 2%

- Trade: 7%

- Transport / Distribution: 4%

- Other: 10%

Next generation owners: 85% (yes), 15% (no)

Have worked in family business: 80%

Headquarter location:

- Republic of Ireland: 62%

- Northern Ireland: 20%

- Other: 18%

Number of siblings:

- 0: 5%

- 1: 28%

- 2: 36%

- 3: 18%

- 4: 8%

- 5 or more: 5%

Birth order:

- 1st born: 41%

- 2nd born: 35%

- 3rd born: 15%

- 4th born: 5%

- 5th born or higher: 4%

Average CEO age: 54 years

72% believe the next CEO will be a family member

What most influences choice of successor?

- Level of interest in the business

- Level of experience

- Level of qualification

- Level of entrepreneurial drive

- Order of birth

33% have a succession plan in place

Top 3 obstacles to succession

- Availability of talent

- Successor selection

- Access to finance

48% disagree education choice connected to family business career

1 in 2 seriously thought of taking over the family business

Succession intentions

Expert commentary from Dr Eric Clinton, NCFB Director and Associate Professor of Entrepreneurship, DCU Business School

Dr Eric Clinton, DCU Business School

Investing in family succession promotes long-term benefits conducive to the family business’s continued competitive advantage and business growth. Effective succession planning stabilises and preserves family relationships and values that are important for enduring turbulent times. For example, recall the resilience of Irish family businesses during the recent Covid-19 pandemic and their fortitude in the face of Brexit.

Emerging research on succession has produced several new but counter-intuitive findings. The typical ‘primogeniture rule’ for succession – choosing the firstborn child to lead the family business – is no longer considered the best (or most equal) strategy for selecting an experienced and talented successor in our complex world.

Many studies show that other succession factors (for example, emotional commitment and the role of business exposure) partially predict the next generation’s succession intentions. The effect is stronger for sons than for daughters, while birth order has no effect. Others indicate that strong intergenerational or intragenerational bonds, as well as imprinting as it relates to legacy, stewardship or psychological ownership, may play a role. This all-island study examines the potential role that these contemporary possible factors might play in enhancing, or suppressing, the succession intentions and aspirations of next-generation members.

- ‘Their father and grandfather before were some of our finest entrepreneurs. Will they be as good as their old man?’

- ‘I wonder if they have what it takes?’

- ‘How will their qualifications assist our firm?’

- Forty-eight percent have seriously thought about taking over their family’s business. Forty percent have strong intentions to become a successor in their family’s business one day, especially male potential successors, whose intention is twice that of women.

"This business is my life. I know that you obviously have to be careful to not let your personal emotions affect it. Dad’s so good at that. He would always, I suppose, put the business first. He’d obviously be very emotionally attached to it, but the business would always come first."

Roisin Lennon, first-year DCU Business School student

The findings of our study highlight a number of trends for Irish family businesses and next-generation members, including the following:

- The average chief executive officer (CEO) age for Irish family businesses was 54 years, and 33% of family businesses have a succession plan in place.

- Seventy-two percent of the next generation think it likely that the next CEO will be a family member.

- The level of interest in the business was judged as being the most likely factor to influence the choice of successor, and order of birth the least likely factor. The factors were ranked as follows in terms of likelihood of influencing the choice of successor:

- Level of interest in the business

- Level of experience

- Level of qualification

- Level of entrepreneurial drive

- Order of birth.

The obstacles that the next generation rated most likely to prevent the succession process from running smoothly were availability of talent, successor selection and access to finance, with tax reasons rated the least likely to affect succession.

The industry does not matter, nor does the size of the business or the generations involved. All successors in a family business will be judged by numerous stakeholders both within and outside of the family business, including family members, employees, directors, the management team, suppliers, customers and investors, among others. Gaining an awareness of how you, as a next-generation member, will be judged and by whom is an integral step on the succession journey of next-generation members.

Test yourself: The Four Tests of a Prince9

Professor Ivan Lansberg wrote a seminal piece in Harvard Business Review discussing the four tests a next-generation member must embrace. These tests represent the trials that leaders must go through to earn the respect and trust of stakeholders in the firm. The four tests are as follows:

- Qualifying tests involve assessments to judge next-generation members’ capabilities and leadership potential Criteria include formal education, work experience, and military and community service, as well as evidence of professional development. Consider any notable on-the-job achievements, such as successfully completing complex projects and board experience. Recognition valued by the business world demonstrates a successor’s potential, easing concerns about their suitability for the role. Possessing a good track record in non-family organisations will reduce doubts regarding suitability for a leadership position in the family business.

- Self-imposed tests highlight the expectations that next-generation members set themselves, against which they expect internal and external stakeholders in the family business to judge them. When setting out their vision for the business, next-generation members’ aspirations to evolve the business should set out the metrics against which stakeholders can measure their effectiveness as a leader, and their ability to earn trust and credibility. For example, when setting out policies on punctuality, hiring, punishment and dismissal, and handling conflicts of interest, stakeholders expect next-generation members to not only ‘talk the talk’ but equally to ‘walk the walk’, and to follow through on their commitments.

- Circumstantial tests prompt next-generation members to embrace unplanned challenges. Traumatic periods in the life of a family business bring leadership into focus and provide opportunities for leaders to showcase their capabilities (for example, think of the recent Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit). These unexpected challenges will prompt stakeholders to assess the strength of the new leader.

- Political tests examine the bitter reality for next-generation leaders about the realisation that not everybody will like them, nor will everybody want what’s best for them. Some stakeholders within the organisation will actively seek to block the implementation of the new leader’s plans, sometimes spreading malicious rumours to undermine the leader’s credibility. Generating awareness of the intentions of members within the organisation is a skill set that next-generation leaders will need to acquire.

9. Lansberg, I. (2007). The tests of a prince. Harvard Business Review, 85(9), 92.

Listen to world-renowned scholar, Professor John Davis of the MIT Sloan School of Management, speak about the enduring advantage of family businesses (YouTube MIT Sloan Alumni, 2018). These lessons will be invaluable as you commence on your succession journey. 10

10. MIT Sloan Alumni. (2018, June 07). The enduring advantage of family businesses [Video]. YouTube.

- Be honest with yourself. Take the time to reflect on what it is you want from the family business, be that as an employee, executive, owner, family council member or board member. Being true to yourself and your aspirations is a fundamental first step. It often begins with completing the simple task of writing down your personal values and what you would like to achieve in your career; consider working in blocks of 5 years. Also be aware of the various roles in the business, as there are often a lot more opportunities than may first appear.

- Make a conscious effort to speak to other next-generation members in family firms in your community. Listen to their aspirations and anxieties, learn from their approach to success and gain insights into their family business network, all the time building your knowledge of the idiosyncrasies of the family business.

- Reflect on the qualifying, self-imposed, circumstantial and political tests that you, as a next-generation member, will face on joining the family business. Consider how you can prepare for the tests and any pitfalls you may need to overcome.

Eleanor and John Patrick Hanna

In 1921, David Hanna cycled more than 100 miles from Belfast to Donegal to secure an apprenticeship with McDaid’s Tailors in Donegal Town. Three years later, he established Hanna Hats. The business initially focused on tailored suits, but over time it evolved to specialise in handcrafted hats and caps.

Today, this family business is managed by Eleanor and John Patrick Hanna, who continue to innovate while also respecting the traditions started by their grandfather. The hats are still handcrafted in Donegal Town by a team of skilled cutters and machinists using high-quality woven tweed. Many of the production processes used by their skilled craftspeople are the same as those used when David Hanna started the family business.

"I wouldn’t have much interest in joining the business full-time right now, but later down the line I’d have no problem leaving whatever job I am in, because I’d far rather it [stay] in the family."

Dáithí Ward, first-year DCU Business School student

Dr Ian Smyth, Ulster University

Formal education and hands-on experiences

Expert commentary from Dr Ian Smyth, Director of the Centre for Sustainable Family Enterprise, Senior Lecturer, Ulster University

Family businesses especially excel at continuing with education from one generation to the next because parental emotional support and access to financial capital or assets endows them with a capability for lifelong learning.

Being raised in a family business environment and working in the business, as most of our next-generation respondents have, promotes a significant (but not strict) bearing on a child’s development and career progression choices. Family businesses appear to understand that a mentoring relationship and education go hand in hand in succession planning and choice. Higher education particularly endows attributes that are important for steering a business through disruptive times; it facilitates accurate analysis of situations, anticipation of challenges, lifelong learning, adaptability and creative problem-solving. A solid educational foundation provides the next generation with the tools to make informed decisions, implement strategic initiatives and adapt to the evolving needs of the market. It has the power to fast-track next-generation leaders to shape an enterprise’s future success and sustainability. Learning from hands-on experiences within the family business is vital. Apprenticeships, internships and active involvement in various business functions allow successors to gain practical insights into the business’s day-to-day operations, understand its organisational culture and develop a deep appreciation for the nuances of the industry in which it operates. Understanding what makes a family business unique is important to consider: is it the reputation, customer service, reliability, location or quality of offering?

The majority of next-generation members expressed strong agreement that family influence and parental emotional support had a significant influence on their career development:

- While encouraging education at school level, parents do not appear to have been ‘pushy’ when it came to deciding what course to take at university level.

- Seventy percent of next-generation members agree that their parents encouraged them to learn as much as they could at school.

- Sixty-seven percent agree that their parents actively encouraged them to achieve good grades at school.

- Sixty-four percent of next-generation members strongly agree that their parents told them they were proud of them when they did well at school.

These findings suggest that parental emotional support has a lasting influence on the career development of next-generation members of Irish family businesses.

- Thirty-four percent agree that their choice of education is connected to their career path in the family business.

- Forty-eight percent of students agree that formal education is connected to their career path in the family business, with a notable leaning towards business-related subjects.

- Comments like the following were regularly heard during our interviews: “I knew I wanted to work in [company name], so I did a course that would fit. So, yeah, I specifically did business so that I will be working there.”

Research shows that mentoring11 acts as a powerful source of learning for successors. Seasoned family members or industry veterans can provide invaluable guidance, sharing their wealth of experience, lessons learned and strategic insights. Mentorship fosters a personalised learning environment, offering successors the opportunity to navigate challenges with the wisdom and perspective of those who have successfully managed the business before them. Legacy in family business serves to connect the firm’s core purpose, family values and meaningful achievements across generations. Families looking to preserve the legacy of their business need to consider how shared values, culture and long-term vision form part of their succession plan. Consider how you will actively pass on the legacy, as it may start by asking next-generation members to formalise the firm’s history and share the family story with the wider family.

"It is successful and it’s always been run well. And my dad, I’ve learned a lot from him over the years, so I think to even get to work with him, to learn more about it and get it on a bigger scale would be completely beneficial…. I think it would be a shame, both for us and for him, if it wasn’t kept within the family. And I suppose it’s just quite an abrupt end if you just sell the business and it’s gone. So, yeah, I would like [it] to stay in the family." Sarah Jane Dunne, final-year DCU Business School student

Family businesses transition through four distinct stages that each present unique paradoxes, priorities and pathways for development. The 4-L framework developed by Moores and Barrett (2010) speaks to these four stages, which are ‘Learn Business’, ‘Learn Our Family Business’, ‘Learn to Lead’ and ‘Learn to Let Go’.

Learn Business (L1) allows family business leaders to develop the distinct skills and capabilities required to lead the family business successfully. At this stage, it can be difficult to decide whether it is best to acquire these necessary skills inside or outside of the family business boundaries. Such learnings can include formal education (e.g., a university degree), industry programmes and apprenticeship. Going outside of and eventually returning to the business offers both opportunities and threats to its family nature. Learning can come through various routes and from various channels.

Learn Our Family Business (L2) requires the next generation to learn the values, tradition and legacy of the business and consider the ways they want their family business to continue differently. Importantly, learners need exposure to real challenges with bottom-line accountability as part of this phase rather than solely budget responsibility. Next-generation members need to know about what makes the family business distinctive and the source of its success: is it the quality and freshness of the food, the customer service provided, the idyllic location, or the family brand associated with the business?

Learn to Lead (L3) is the phase in which leaders in the family business begin to introduce governance structures in the business across the family, the ownership group and the business. Such governance structures across each sphere create vehicles to have difficult conversations while also increasing transparency in the business. Such structures will also facilitate the flow of information and communication between the family, the business and the owners. They may include a family employment policy or a family constitution in the family sphere; a shareholders’ agreement and ownership policies (including dividend and risk) in the ownership sphere; and a board of directors and non-executive directors in the business sphere.

Learn to Let Go (L4) is the final phase, which must occur gradually. Family leaders must foster convergence of thought within the firm as well as mobilise internal change agents. Incumbent leaders need to plan their exit and consider how they can set the next generation up for success.

Suggested reading: “The 4-L framework of family business leadership” by Professor Mary Barrett.

- Next-generation members should learn about your family business by identifying its source of success, whether that is the quality of the offering, customer service, location, fresh produce, reliability, speed to market, etc.

- Next-generation members should identify your sources of mentoring and support – from within the family as well as from outside of the family enterprise – in order to meet the demands of the business as it evolves.

- Incumbent leaders should invest in your successor’s formal and experiential learning journey to encourage a continuous culture of learning. Readiness for new innovation will help your business remain competitive.

Patrick Tinnelly, Martin Tinnelly, Dessie Tinnelly

The Tinnelly Group is a multidisciplined specialist contractor providing demolition, asbestos removal and metal recycling services. It has a distinguished trading history spanning multiple generations, and for almost six decades, the Tinnelly Group has been demolishing the old to make way for the new.

From city centre high-rise structures to major industrial facilities and everything in between, the Group has been at the cutting edge of the regeneration of Ireland’s towns and cities.

Investment in the best people, training and equipment has enabled the Tinnelly Group to forge a reputation as an industry leader, and the Group’s extensive experience and expertise has allowed it to maintain its position as one of Ireland’s leading specialist contractors.

"My aspiration to work for Tinnelly Group derives from the unique opportunity to contribute to a legacy built on family values and a chance to work closely with relatives who share the motivation to see the business continue to succeed in the industries in which it operates. My study of law has heightened my ambition to be a part of the next generation, as I believe I will provide valuable legal knowledge such as risk management, and the ability to adapt to evolving markets through problem-solving and analytical skills."

Cliodhna Tinnelly, first-year Ulster University student

Dr Catherine Faherty

Responsible Nepotism

Expert commentary from Dr Catherine Faherty, NCFB Associate Director and Assistant Professor of Enterprise, Dublin City University

The term ‘nepotism’ describes the practice of showing favouritism based on familial relationships. It involves situations where individuals such as the boss’s son, daughter-in-law, nephew or cousin are hired or promoted over more qualified candidates.

Nepotism often contradicts our innate sense of fairness, eliciting frustration and resentment towards those who engage in it. Nevertheless, in family businesses, nepotism is frequently accepted as a standard practice. This is because parents in such enterprises typically aim to build a prosperous business to pass down to their children for subsequent generations.

However, this practice can pose significant challenges when the beneficiaries lack the necessary qualifications or skills for their roles. Additionally, long-serving non-family members may feel disenfranchised when family owners deliberately groom their children to assume their positions. Instead, family businesses should practise what could be termed ‘responsible nepotism’. This entails ensuring that family members, like their non-family counterparts, are genuinely qualified to fulfil their roles. They should undergo appropriate schooling and training, acquiring the requisite understanding, skills and ethical standards relevant to their positions or trades.

The majority of next-generation members expressed disagreement with the notion that family members receive preferential treatment over non-family members in their family’s businesses:

- Forty-three percent disagreed with the idea that family members are treated more leniently than non-family members in their businesses, with 30% agreeing and 27% remaining neutral on the issue.

- Forty-two percent disagreed with the notion that the perspectives of family members take precedence over those of non-family members when making business decisions, while 33% agreed and 25% remained neutral.

- Seventy percent disagreed with the assertion that shortcomings of family members are overlooked within the business, while 12% agreed and 18% remained neutral.

These findings suggest a positive trend: nepotistic tendencies are not perceived as prevalent by next-generation members of Irish family businesses.

Various types of owners are commonly observed in family businesses, including financial and psychological owners. A financial owner typically holds a stake in the business purely from a financial perspective. Conversely, a psychological owner is deeply emotionally or psychologically invested in the business’s success, regardless of whether they hold a financial stake in the business. A fundamental yet seldom examined assumption suggests that fostering a sense of psychological ownership among employees can yield significant advantages without necessitating the financial investment associated with granting them tangible ownership stakes. For instance, research on psychological ownership suggests that employees can develop strong feelings of possessiveness toward “their firm” and that such employees express greater satisfaction, commitment, and job performance.

We asked our next-generation respondents about their ownership stakes, and the results are intriguing.

- The majority of respondents (85%) do not hold a financial ownership stake in their family’s business, with only 15% reporting the possession of ownership stock. This finding aligns with our expectations, considering that the average age of our next-generation respondents is 22 years.

- However, when asked about psychological ownership, 39% of next-generation members reported experiencing a very high degree of personal ownership for the business.

- Notably, when we compared responses between males and females, we found that males were significantly more inclined to feel this very high degree of personal ownership than their female counterparts.

Next-generation members frequently encounter trust-related challenges within the family business. A 2017 global study conducted by Edelman revealed that next-generation CEOs are often trusted less than founders and are perceived as more prone to mismanaging the business. Additionally, long-standing employees often view next-generation members as less passionate, committed and deserving of admiration or respect compared to their predecessors. However, despite these obstacles, next-generation members have the opportunity to address these negative trust perceptions by aspiring to become trustworthy leaders.

Decades of research underscores that genuine trust is established based on three foundational principles:

- Ability, denoting a proficient understanding of the requisite skills for the task at hand and the capability to effectively execute them. Next-generation members can build competence by engaging in ongoing education and professional development to stay abreast of industry trends, best practices and new technologies relevant to the business.

- Integrity, characterised by a steadfast commitment to fulfilling promises and upholding ethical standards. Next-generation members can demonstrate integrity by following through on promises, agreements and obligations, and demonstrating reliability and accountability in all interactions and business dealings.

Benevolence, reflecting a genuine concern for the welfare and equitable treatment of others. Next-generation members can demonstrate benevolence by prioritising the well-being and fair treatment of employees or engaging with the local community through philanthropic initiatives to make a positive impact and give back to society.

Listen to Professor James Davis speak about building trust in the video (TED, 2014). 2

2 TED. (2014, December 06). Building trust [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/s9FBK4eprmA

- Adopt rules of entry that family members wanting to work in the business must adhere to. Such criteria may include mandating a 4-year degree and/or stipulating a period of 2–5 years spent working outside the family enterprise to gain experience in a competitive business environment.

- Develop a family constitution to define family values and establish a collective vision for how the family and business will work together going forward.

- Earning the trust of those around you is essential for effective leadership and fostering positive relationships. Work on cultivating trust through demonstrating competence, integrity and benevolence.

Vincent Hurl, Ciara Hurl, Anna Hurl and Melanie Hurl

The Crosskeys Inn in County Antrim is Ireland’s oldest thatched pub, boasting a rich history dating back to 1654. The pub, under the stewardship of the Hurl family, welcomes both locals and international travellers and is regarded as a ‘must-visit’ destination by esteemed international travel guides, including Lonely Planet.

Among the family custodians is Ciara Hurl, a final-year student of International Hospitality Management at Ulster University. Ciara grew up in the pub and its legacy is deeply ingrained in her. She reflects that it is “almost like another sibling to me. It’s a second home. I adore it.”

For centuries the Crosskeys Inn has served as an important hub for social interaction and shared experiences within the local community. It was once a shop, a post office and a bar. The Hurl family’s presence in the business over the years has allowed them to establish intimate connections with the rural community they serve.

“The customers know me from when I was a baby in a wee carrycot. They’ve seen me grow from a child. They’ve been there for my birthdays, communions, confirmations. They’ve seen everything in my life, and I’ve seen everything in theirs. I’ve seen people meet at the bar, date, marry, have children. Growing up in a family business means you’re such a big part in people’s lives.”

Ciara Hurl, final-year Ulster University student

Dr Roisin Lyons

Expert commentary from Dr Roisin Lyons

Associate Professor of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Kemmy Business School, University of Limerick

Emotion, attachment, obligation and commitment are all facets of succession which can be challenging for parents and children within a family business to grapple with. Often, the children of entrepreneurial families do not intend to take over their parents’ business. Yet, many feel an emotional tie to it regardless.

An individual’s emotional attachment to and identification and involvement with a business or family business is known as their affective commitment to it. Attachment and commitment to the family business typically raise numerous questions for next-generation members:

“Is this something I have to do or want to do?” “What if my parents want me to join the business but I decide it is not for me?” “I am fully committed to the business, but want to spend some time outside to build my credibility. How can I do that?” “Will I gain some of the family’s wealth if I decide not to join the business?”

- Sixty-six percent of next-generation members reported positive feelings of attachment to their family’s business. Nonetheless, 33% of respondents had negative or neutral feelings of attachment towards their family’s business.

- When asked if potential successors felt an obligation to pursue a career in the family business, there was a mixed response, with 30% of respondents in agreement and 44% in disagreement.

- Of the sample, only 11% of respondents felt a strong obligation to pursue a career within the family business.

- In choosing not to take over the family business, 49% of respondents did not fear a potential financial opportunity cost.

- Eighty-two percent of respondents believe that they would be able to find external employment outside of the family business.

Leading family business scholar Professor Pramodita Sharma (Schlesinger-Grossman Chair of Family Business at the Grossman School of Business, University of Vermont) and colleagues pioneered affective-commitment mindsets as the four bases of the family successor commitment framework to better understand succession intention.

These mindsets correspond to the following types of commitments:

- Affective commitment is based on a strong belief in, and acceptance of the family business goals, combined with a desire to contribute to these goals. The successor “wants to” pursue a career in the family business.

- Normative commitment is based on feelings of obligation to pursue a career in the family business. The successor feels that they “ought to” pursue a career in the family business.

- Calculative commitment is based on successors’ perceptions of opportunity or threatened loss of investments or value if they do not pursue a career in the family business. The successor feels that they “have to” pursue a career in the family business.

- Imperative commitment is based on a feeling of self-doubt that one has the ability to pursue a career outside the family business. The successor feels that they “need to” pursue a career in the family business.

Commitment to the family business is considered to be an important factor in motivating the next generation to take over. It has also been shown to be an important factor in overcoming challenges and crises, such as those experienced by many during the Covid-19 pandemic.20

Our study examined if the attachment and commitment family members feel towards each other via succession intent is part of this Irish family business ‘winning formula’. We presented respondents with four statements on successor attachment and commitment: affective (emotional commitment), normative (sense of obligation), calculative (perceived opportunity costs involved) and imperative (perceived need).21

20. Faherty, C., Smyth, I., Farrelly, K., Burrows, S., Crossley, C., McDowell, D., & Greene, L. (2022). Surviving a crisis as a family business: an all-island study. Dublin City University.

21. Sharma, P., & Irving, P. G. (2005). Four Bases of Family Business Successor Commitment: Antecedents and Consequences. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 13-33.

In the interviews, respondents highlighted the nuanced and emotionally laden challenges within succession:

"If you take over, or if you decide to take over, if you decide to get involved, you have that risk that you’re letting somebody down or it’s spent 31 years building a business and you go in and what happens if it just fails after a year or two?"

Jeff Bowers, final-year DCU Business School student

"There is a pressure…and I just don’t know if that’s what my dad wants…so I think to keep him happy, I’d want to do it. But I then need to obviously consider if that would make me happy kind of a thing."

Kelley Higgins, final-year DCU Business School student

Even when considering the option to postpone succession, or take a lesser role, respondents displayed high levels of commitment to the family business.

Learn more about family business commitment by viewing a short introduction video from Professor Pramodita Sharma (Grossman School of Business, 2020). 22

22 Grossman School of Business. (2020, November 10). Professor Pramodita Sharma talks about entrepreneurship in family business [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/xPfhslrtydc

Learn more about commitment and sustainable and resilient family businesses by listening to the Transforming Tomorrow podcast from Lancaster University.23

23. Discua Cruz, A. (Host). (2023, December 18). Sustainable and resilient family businesses [Audio podcast]. Lancaster University Transforming Tomorrow. https://youtu.be/15aJX4y0woU

- Consider which of the commitment types align with your succession intentions – whether joining the business is something you want to do, ought to do, have to do or need to do. Understanding your commitment will typically inform your motivation for joining the family business.

- Work on your communication and emotional support within the family unit. Emotional support from family business parents plays a key role in helping the next generation feel competent and motivated about succession. Parental emotional support can be developed through storytelling, legacy sharing and career development signposts.

- Exposure to the family business, by working in it, has a positive impact on affective commitment. Consider taking a more active role in the business to determine your feelings about the work itself.

Independent Express Cargo

Independent Express Cargo was established in 1984 by Owen Cooke. Initially, the company was focused on general freight forwarding and customs clearance. Today, the Dublin-based family business provides freight, transport and logistics services. As the Dublin member and founder of The Pallet Network Ireland, Independent Express Cargo collaborates with 24 other freight companies to offer the most dependable palletised freight delivery service in all of Ireland.

Cormac Sullivan, a DCU Business School student, has worked part-time in the family business alongside his parents since he was a teenager and has significant memories of it.

I have more memories in the business than without it.

Cormac Sullivan, first-year DCU Business School student

Dr Michelle Cowley-Cunningham

Well-being and sustainable business practices

Expert commentary from Dr Michelle Cowley-Cunningham

A healthy family is crucial to a long-lasting, successful family business. Families placing a high value on their individual and group well-being are ones where members look out for one another, have fun together, communicate effectively and make decisions as a team. Business standards increasingly emphasise the importance of the relationship between well-being and sustainable economic development, as well-being also depends on environmental quality.

Embedding sustainable practices into business is a generational priority, and it is important that next-generation succession planning gives voice to members of the next generation so they can participate in its implementation. Enhanced economic growth is more sustainable when inequality is addressed and environmental quality is improved, as set out by the United Nations SDG framework. Research examining the relationship between sustainable development and well-being finds that countries with a higher SDG Index score tend to do better in terms of subjective well-being – with countries such as Ireland topping international rankings.24

Our research examined if SDGs are likely to be impacted by decisions and leadership direction for Irish family business successors – namely SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production). 25

24 De Neve, J-E., & Sachs, J. D. (2020). Sustainable Development and Human Well-Being. In J. F. Helliwell, R. Layard, J. D. Sachs, J-E. De Neve, L. B. Aknin.

25 United Nations (2018, April 20). Do you know all 17 SDGs? [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/0XTBYMfZyrM

- Employing the Satisfaction With Life Scale26,27 as an international standard indicative of well-being, 90% of next-generation respondents were very satisfied, satisfied or slightly satisfied (score of 16–25, or >15) and 10% were slightly dissatisfied or dissatisfied (score of <15) with their lives. As a group, the respondents were overall satisfied with life at this point (average score of 19).

- Northern Ireland’s next-generation respondents’ well-being scores were also positive and did not deviate from the overall average (average score of 18.86), with men’s and women’s well-being almost equal. Despite the context in which our potential successors negotiate their daily studies and lives, their well-being is robust relative to international standards.28,29

26 Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75.

27 The Satisfaction With Life Scale presents questions asking to what extent respondents agreed with five statements on a five-point scale: “In most ways my life is close to my ideal,” “The conditions of my life are excellent,” “I am satisfied with my life,” “So far I have gotten the important things I want in my life,” and “If I could live my life over I would change almost nothing”. A total score out of a maximum of 25 indicates the degree of the respondent’s life satisfaction.

28 Samman, E. (2007). Psychological and subjective well-being: A proposal for internationally comparable indicators. Oxford Development Studies, 35(4), 459-486.

29 Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 69(5), 851.

- Respondents in this study ranked contributing to decent work and economic growth as the most important SDG of the three evaluated, should they become a successor in their family’s business.

Global studies demonstrate that as responses to sustainability initiatives improve, SDGs align strongly and positively with higher well-being globally, particularly SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth). Our research found a connection between the next generation’s SDG aspirations and their reported well-being.

The connection between next-generation members’ overall succession intentions and their aspiration to implement SDGs in the family business was also strong. Our research suggests that the intention to become a family business successor is related to making a positive impact on the environment.30

30. For example, see Cowley-Cunningham, M., Carey, A., & Rogers, E. (2023). The Climate Crisis, Climate Anxiety and Children’s Rights: A Psychological Perspective on Human Health and Security. Irish Studies in International Affairs, 34(1), 111-123.

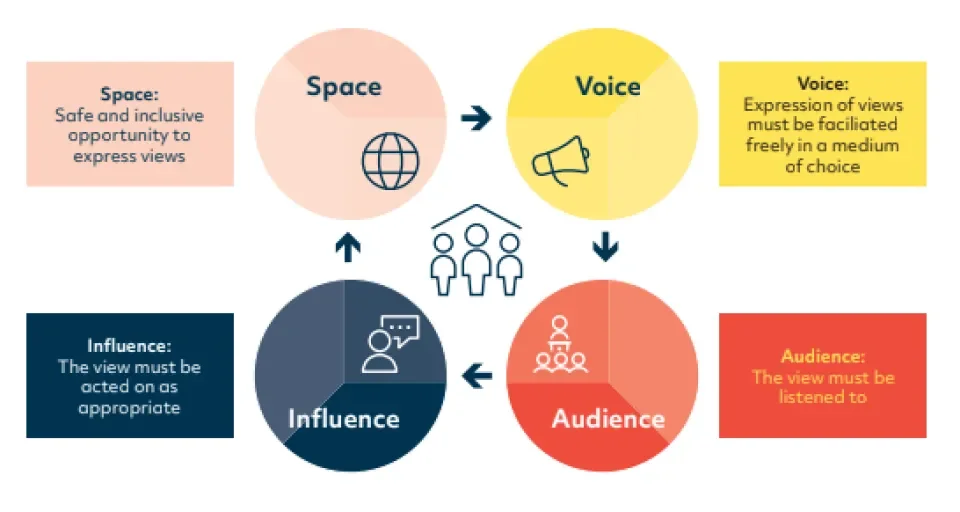

Next, we present a quick and easy-to-use model demonstrating the key components for creating participative voice in order to enable the next generation to take part in family business decision-making and sustainability.

The succession planning process provides a key opportunity for next-generation members to activate their right to participate in family business decisions concerning them, especially legal ones.

Figure 2: The Lundy model of participation for the family business

Source: Adapted from Lundy (2007)32

Research shows that children’s and young people’s understanding of how their choices interact with business to impact on the environment is greatly underestimated.31

The model in the graphic (left) visualises best practice to help you facilitate next-generation members’ participation in decisions relevant to their future.

31. United Nations. (2022). Report of the first Children and Young People’s Consultation on General Comment No. 26, September 2022. https://childrightsenvironment.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Report-of-the-first-Children-andYoung-Peoples-Consultation.pdf

32. Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927-942.

1. Space: Enabling next-generation members’ participation rights in succession dialogue, via membership of the family council, may result in creative solution development to counteract business practices damaging to the environment.

2. Voice: A positive attitude towards, and listening to, next-generation members’ ideas about implementing sustainable solutions in family council meetings is important. It may also ease any negative feelings they have about aligning their future with the family business.

3. Audience: Involve next-generation members in drawing up transition plans for sustainable business practices, especially the issues they express voice on at family council meetings. This will

demonstrate that their voice is authentically valued.

4. Influence: Make explicit the role of next-generation members by establishing a decision-making process that includes them; be it via family council or other one-stop initiatives.

1. Involve the next generation in family business decision-making by drawing up a family business constitution reflecting a sustainability mindset.

2. Enable next-generation members’ participation in family

council proceedings and allow them to share their voice in drawing up the family business succession plan.

3. Focus on the next generation’s well-being by checking in with them regularly about how their studies are progressing. Be mindful of how their higher education choices may be helpful to the family business, but also be open to a conversation about allowing them to choose their own destiny.

Tusker Construction Group

Established in 1995, Tusker Construction Group is an award-winning family business specialising in construction, demolition, crane hire and civil engineering. In addition to its exceptional work, Tusker is also dedicated to the well-being of its employees and has even established its own apprenticeship and training programmes.

Tusker’s commitment to its workforce has been recognised with the title of Workplace of the Year 2023 from the Irish Steel Awards. Roisin Lennon, whose grandfather, uncle and father founded the company, is proud to be part of the family business and decided to study business at DCU so she will have the necessary skills to work at the company. She understands the value of a content and satisfied workforce.

It’s important to keep our employees happy and content

because they are the most important people in our business.

– Roisin Lennon, first-year DCU Business School student

John McGeown

Incorporating sustainability into family business succession

John McGeown, Head of Sustainability, AIB

Family businesses represent a cornerstone of the Irish economy and are renowned for their strong value systems, community-oriented approach, and long-term perspectives. These characteristics inherently align with the principles of sustainability, which emphasise long-term environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and naturally economic viability.

Family business succession is a delicate process, presenting an opportune moment to deeply embed sustainable business practices. However, blending intergenerational perspectives and vision is not without its challenges.

Understandably, hard fought business success sometimes comes with a reluctance to incorporate change, especially when benefits

are not immediately evident. Additionally, the up-front costs associated with implementing sustainable practices may be daunting and require a long-term and strategic perspective. Patient intergenerational dialogue is therefore crucial when considering sustainability strategies that both honour the past and embrace the

future.

As with any fundamental strategic change, family business succession is an opportunity for the reassessment of business strategies including the incorporation of more sustainable practices. These challenges will in turn present opportunities for dialogue, education, and collaboration which can ultimately lead to stronger, more unified family businesses. Indeed, many have already introduced sustainable

practices into their operations without realising it— meaning evolution rather than revolution is often required.

For businesses yet to incorporate sustainability into their operations, it is important to call out that avoiding sustainable action will become more difficult in the years ahead. This shift will be driven by legislative change in the form of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). The CSRD is EU legislation which came into force in 2024 and will increase the scope of ESG reporting requirements for businesses across Europe.

The CSRD requires full value chain assessment for businesses putting an onus on small businesses, which are not directly in scope, to identify and report a range of ESG data to their key customers.

Ultimately, the CSRD will see the language of sustainability, and the reporting of data associated with it, become business as usual. Demonstrating a sustainable business operation is set to become a core necessity when tendering for new contracts and will even affect the retention of existing business. This reality, coupled with societal awareness of the importance of sustainability, will ensure it is a key consideration for all businesses across the Irish economy.

- 62% agree that involvement in their family business will allow them to positively contribute to sustainable cities and communities.

- 76% agree that joining their family business will allow them the opportunity to create decent work for employees.

- 69% agree that involvement in their family business will afford them an opportunity to promote responsible consumption and productivity within their communities.

These findings suggest a positive trend: that sustainability, and the opportunity to influence communities through their family business is important for next generation members of Irish family businesses.33

33 Clinton et al. (2024). To join or not to join? Understanding the succession intentions of next-generation family business members. National Centre for Family Business Policy Report Commissioned by AIB. Dublin: Dublin City University.

As a financial institution at the heart of the Irish economy, AIB has an important role in supporting our business customers as they transition to more sustainable operating models.

Our approach to this is two pronged:

Firstly – when capital is required for sustainable investment, we have a range of solutions suitable for our business customers. These solutions can range from supports for smaller businesses beginning their sustainability journey, to those for larger entities further along their path.

Secondly – we also aim to play a key role supporting our customers by providing the information and education to guide them on their sustainability journey. This approach has seen the AIB publish a suite

of sector sustainability guides, which provide practical tips and information on sustainability and can be viewed on the AIB website.

Furthermore, AIB has partnered with sustainability educational providers Greentech HQ and Dublin Chamber Sustainability Academy. These partners support our business customers to demystify the topic of sustainability and translate it into tangible actions and strategies.

Finally, there exists a unique synergy between sustainability and family business succession. It presents a dual possibility of forging a path towards a more resilient and eco-conscious future, for both businesses and the wider economy. Family businesses are fast seeing themselves at the forefront of sustainability, preserving their legacy and actively shaping a sustainable path from one generation

to the next. Adopting sustainable practices will therefore continue to ensure their longevity and relevance to the Irish economy and its future generations.

Network International Cargo

Network International Cargo (NIC) is a global logistics and distribution services company headquartered in Dublin. Established in 1993, NIC has grown significantly since its inception and now operates across Ireland, the UK and Europe.

The company is dedicated to providing best-in-class service to its customers and enhancing the skills and abilities of its employees. To accomplish this, it created a Team Development Programme that focuses on areas such as communication, personal growth, staff motivation and people management. Moreover, the company is taking measures to reduce its carbon footprint by investing in solar panels and new hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO)-fuelled vehicles.

Dr Linda Murphy

It’s all about the money – or is it? The non-financial goals of family business

Expert commentary from Dr Linda Murphy

For family businesses, being in business is about more than just making money.34 Decades of research has shown that family businesses pursue non-economic goals as well as economic goals.35

While financial viability ensures survivability, family businesses are committed to continuity, valuing the non-financial benefits their reputation and relationships bring.

These benefits include the level of family influence on the business, identification with the business, positive emotional attachment, social connections or relationships derived from its network, and stability through commitment to succession.

Family business members derive these non-financial benefits from being part of a family business, the results of which are termed socio-emotional wealth (SEW). The non-financial benefits of being part of a family business, reflected in their SEW, was very important to our next-generation members and it is something they wish to perpetuate across generations. Our next-generation members were acutely aware that SEW is something that makes them unique as family businesses. Concerns about non-economic goals, community affiliation and family business identity raise numerous questions for next-generation members, including:

- What role can I play to maintain our positive reputation and community affiliation, regardless of whether I enter the business?

- How can I contribute to and enhance our commitment to our non-economic goals to maintain our stock of SEW?

- In my role as a next-generation family member, how can I influence our SEW?

34 Diaz‐Moriana, V., Clinton, E., & Kammerlander, N. (2024). Untangling goal tensions in family firms: A sensemaking approach. Journal of Management Studies, 61(1), 69-109.

35 Debicki, B. J., Kellermanns, F. W., Chrisman, J. J., Pearson, A. W., & Spencer, B. A. (2016). Development of a socioemotional wealth importance (SEWi) scale for family firm research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(1), 47-57.

- Seventy-three percent agree that their family business is recognised for positively contributing to the local community. During our interviews, we regularly heard about sponsorship of local GAA teams, scouts, and church, as well as serving on community boards and councils.

- The majority of our next-generation respondents grew up in the business and learned about the importance of hard work and the responsibility that comes from being part of the family business.

Next-generation members also feel strongly about protecting their family’s reputation, indicating that preserving the opinion of others is of consequence (73% versus 9%, with 18% remaining neutral). They deem the social relationships earned from being a part of the family business to be important and meaningful (87% versus 2%, with 11% remaining neutral).

I think there’s kind of like a culture of trying to shop local and support local businesses. So, I think that kind of gathers, like, a good kind of sense of community and things like that. And he’d [father would] be known in the business or in the community, should I say, for this business, and say if people need favours, if they need anything, that he’d be willing to kind of help them, or maybe he’d give discounts to family and friends and that kind of thing. So, I think he’s kind of gathered a good sense of like a businessman, kind of like a good name in the community, which I think is nice as well.

– Kelley Higgins, final-year DCU Business School student

Seventy-six percent agree that the family has a strong influence on the values of the family business.

Seventy-six percent of respondents agree that retaining family unity is a top priority in their family business.

SEW provides a consistent strategic reference point for decision-making in family businesses. Family businesses can make decisions to preserve their SEW, which, at times, can impact on their financial gains both positively and negatively. Research also shows that SEW influences the life path of next- generation family business members because of their emotional attachment to, and identification with, the business from a young age.36

Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that SEW declines across multiple generations. An easy way to remember the five major SEW components relevant to family business is by using the mnemonic ‘FIBER’, where each letter represents a core component:

F: Family control and influence

I: Identification of family members with the business

B: Binding social ties

E: Emotional attachment of family members

R: Renewal of family bonds to the business through dynastic succession

36 Murphy, L., Huybrechts, J., & Lambrechts, F. (2019). The origins and development of socioemotional wealth within next-generation family members: An interpretive grounded theory study. Family Business Review, 32(4), 396-424.

Further reading:

- Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez-Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25(3), 258-279.

- Enterprising Families Podcast 37

37 Venter, E. (Host). (2020—present). Enterprising families podcast [Audio podcast]. Spotify.

- Involve the next generation in the family business from a young age. This can help to develop their emotional attachment and sense of identification with the business, which leads to the development of SEW.

- SEW has benefits for the next generation and the business. Regardless of their succession intentions, encourage the next generation’s involvement in the business so that they become personally invested in protecting the image and reputation of the business.

- SEW can be both a burden and a virtue for the next generation, which is important for family business owners to be aware of. Engage next-generation members so they understand the experienced burdens of SEW.

Ben and Dympna Fitzgerald with Margaret Considine, President of the All-Ireland Business Foundation

Totalcare is a multi-award-winning Irish beauty company that was founded in

1983 by Dympna Fitzgerald, who has devoted herself to providing permanent

hair removal and aesthetic care since then. This family business is now in its second generation, with Dympna’s son Ben working alongside her.

Initially focused on providing treatments directly to clients, this family business has since diversified its portfolio of products and services. Firstly, Totalcare runs an academy to train the next generation of beauty therapists; secondly, Totalcare has a clinic where it shares its expertise with clients; and thirdly, it sells cosmetics and distributes aesthetic equipment and cosmetics for retailers.

In terms of what the business means, what we want to do, the clue is almost in the name, total care. We totally care...whether it’s dealing with the customers, whether it’s dealing with our employees, whether it’s dealing with any stakeholder, we come from a place of caring and we want to have that positive, sustainable relationship.

– Ben Fitzgerald, PhD University of Limerick student

To assist next-generation family business members in their succession journey, we have included three workbooks for you to complete. The workbooks will benefit your engagement with your family business through a number of activities, including crafting your transition plan, identifying areas of competence, preparing for mentorship, aiding dialogue in family council meetings, and identifying the expectations you and others have.

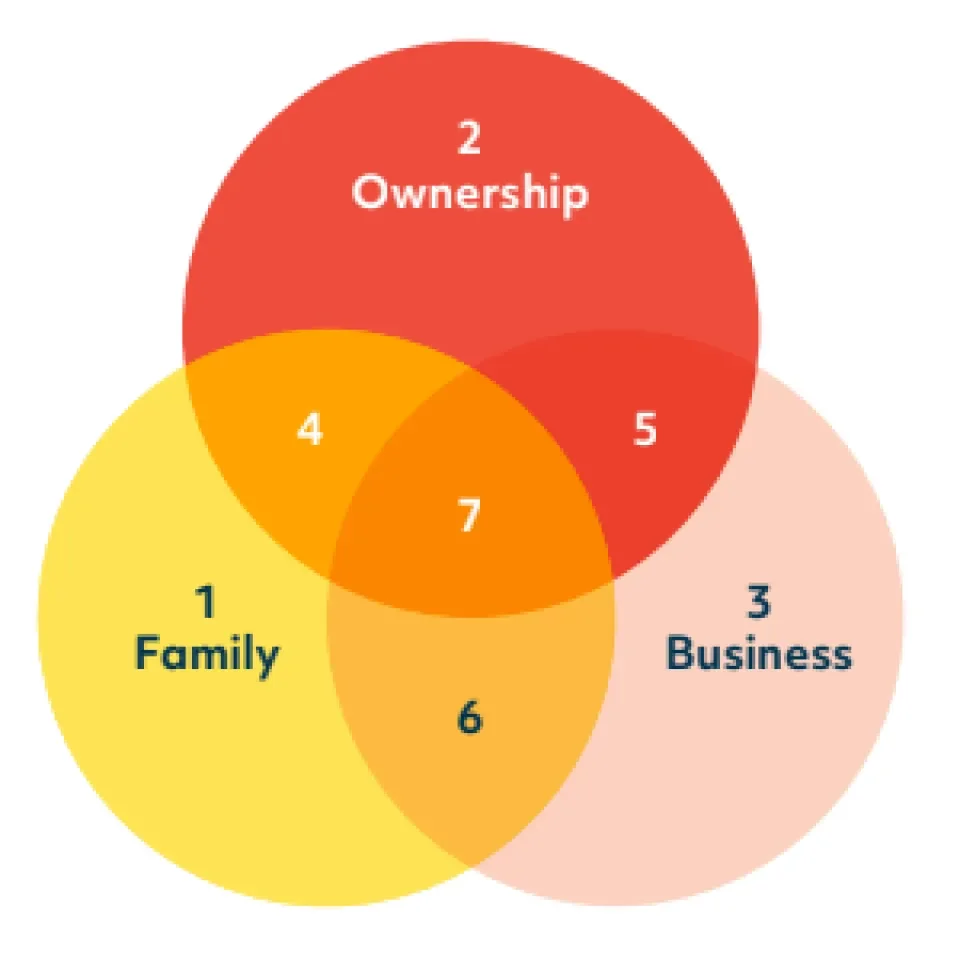

The three circles in the diagram below represent the web of relationships between family shareholders, non-family shareholders, family management, non-family management, family employees and non-family employees, as well as outside family members with a vested interest in the business. These relationships are complex and often restricted, but dynamic.38

They require careful consideration or management in tandem with running a business well. These relationships are the spaces where

problems/challenges for family businesses – including succession planning – emerge, and are also where entrepreneurial solutions are

provoked and offshoots enabled.39

Next-generation offshoots can lead to prospective commercial growth and continuity of the family legacy in new businesses operating within (to create innovative solutions) and outside (to grow or to absorb problems for the business elsewhere) original intergenerational lines.40

38 Cambridge Family Enterprise Group. (2018, October 23). Three-Circle Model: Building Effective Groups in the Family Business System [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/lanT-HQha28

39 Radu-Lefebvre, M., Ronteau, S., Lefebvre, V., & McAdam, M. (2022). Entrepreneuring as emancipation in family business succession: a story of agony and ecstasy. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 34(7-8), 582-602.

40 Baù, M., Chirico, F., Pittino, D., Backman, M., & Klaesson, J. (2019). Roots to grow: Family firms and local embeddedness in rural and urban contexts. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 43(2), 360-385.

Figure 3: The Three-Circle Model of Family Business Source: Adapted from Cambridge Family Enterprise Group (2018)

Within the Three-Circle Model, one can depict seven distinct interest groups (or

stakeholders) with a connection to the family business:

- Family members not involved in the business, but who are descendants or spouses/ partners of the owners

- Non-family owners who do not work in the business

- Non-family employees

- Family owners who are not employed in the business

- Non-family owners who work in the business

- Family members who work in the business but who are not owners

- Family owners who work in the business

Task to undertake:

- Draw out the three circles on a blank page.

- Identify where you are positioned.

- Identify other members on the diagram (e.g., “my sister is a ‘family owner’: she is family and she has ownership but does not work in the business”). When you have identified individuals across the circles, then begin to explore their aspirations and concerns.

By undertaking this task, you will begin to understand the perspectives of other stakeholders; it will allow you to empathise with other stakeholders and to bring them as ‘followers’ on your journey.

We recommend you watch Professor John Davis’ supporting video ‘Three-Circle Model: Building Effective Groups in the Family Business’ (Cambridge Family Enterprise Group, 2018).41

41 Cambridge Family Enterprise Group. (2018, October 23). Three-Circle Model: Building effective groups in the family business [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/lanT-HQha28

Building on the recommendations from Theme 1 on the topic of succession intentions, complete the following workbook: