Handwriting or type: what's the future of learning Chinese?

Analysis: learning Chinese means studying the sound, shape and meaning of each character

Brainstorm readers may remember that Caitríona Osborne recently pointed out the unique features of the Chinese writing system which have led it to be considered difficult to learn. One aspect of Chinese that is different from English is the relatively unsystematic and unreliable association between the sound and the shape of a word or a Chinese character.

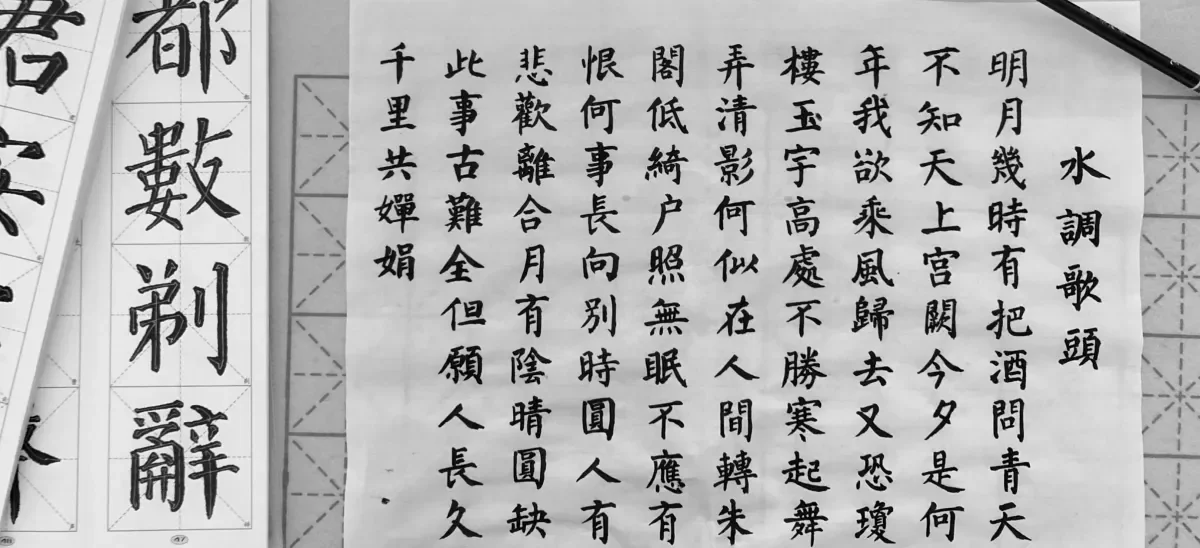

As shown above, it is unlikely that someone could guess that the written form of "mā" is 妈 (meaning mother), based only on its pronunciation. In other words, learners of Chinese need to study all three integral parts of each Chinese character: the sound, shape and meaning.

Furthermore, handwriting in Chinese requires attention to character composition and the pairing of the writing movement with the language stimulus – the Chinese character. This pairing can contribute to long-lasting motor memories of Chinese characters and therefore offer additional assistance for character recognition. For this reason, the write-to-read effect makes handwriting necessary in the study of Chinese.

But the usefulness of handwriting in the digital era has been questioned in recent years, since typewriting using keyboards is more attuned to contemporary lifestyle. In China, children are usually taught to type on a computer and touchscreen during the third year of primary school. Even some Chinese language proficiency tests are computer-based nowadays, requiring learners of Chinese to use input software to type Chinese. For example, the widely known HSK test (mainland China’s national standardised test of Chinese language proficiency, which is also available to learners of Chinese in Ireland) offers a computer-based mode which allows the typing of Chinese to answer questions.

There are generally two types of Chinese input: pinyin input and component input. The former entails typing Chinese pinyin – a Romanised form representing the sound of each Chinese character – and then choosing the intended option from a list of homophones. The picture below shows how to type "mother" using the Google pinyin input method. We type the pinyin "ma" and then select the correct character. In this case, it ’s number four on the list generated by the software. Component input entails drawing the basic structure of a character and then selecting the correct option from a list of characters with a similar structure provided by the input system.

One similarity between these two input methods is that neither encourages memorising whole character representations, especially when a fuzzy matching technique is embedded in the input system. That is to say, even if pinyin is not fully or correctly written, the pinyin input system is still able to find the most similar pronunciation. Likewise, for the component input method, a list of computer-generated possibilities can be shown to users for selection even if a character is not structured properly.

On the one hand, typewriting, which does not require memorising every single detail of a character, can help reduce the anxiety and frustration associated with learning Chinese characters. It also equips learners of Chinese with the ability to communicate in the digital world. On the other hand, concerns have been raised regarding the potential negative impact of typewriting on Chinese learning in the long term, due to reliance on auto-correction and software-generated possibilities. A study conducted by the author shows that adult learners of Chinese are usually aware of the pros and cons of handwriting and typewriting, and demonstrate their desire to maximise the benefits of each writing modality for their study of Chinese.

Indeed, with the frequent use of electronic devices for communication nowadays, it is no longer a question of whether typewriting should be included in a language learning curriculum. Rather, the central questions are when and how to teach typewriting to language learners. Research carried out by the author has found that it would be beneficial to introduce typewriting at pre-intermediate level in the specific context of learning Chinese as a foreign language, when learners already have a solid language foundation. Instead of spending time on micro-level details, learners are then able to allocate more of their attention to relatively high-order thinking, such as choosing appropriate vocabulary, structuring sentences properly, and planning the best way to present ideas in a logical order.

After introducing Chinese as a two-year state-examined subject, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) recently released a draft specification for Leaving Certificate Mandarin Chinese. There are a number of items that need to be discussed and clarified, such as the number of characters to be taught at this level, the actual content covered in the course and the medium of instruction.

Interestingly, the draft specification states that "students will be … familiar [with] digital scripts including the most commonly used fonts for Mandarin Chinese". It might be too early to introduce typewriting on the Leaving Certificate course, as the foundations of the writing system are not yet solid for students. But it is a good idea to at least allow learners of Chinese to be exposed to the digital scripts which may prepare them for future learning through typewriting.