Inaugural Conference

Climate Action: Ireland’s Role in a Changing World

The inaugural DCU Centre for Climate and Society conference took place on May 5, 2022 on the DCU St. Patrick’s Campus, with a keynote address by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins. The conference programme can be seen here.

Dr David Robbins, Director of the DCU Centre for Climate and Society

Dr David Robbins, Director of the DCU Centre for Climate and Society, welcomed the audience of 400 attendees. He said the impetus for the Centre came from a conviction that “more facts” from the physical sciences had not led to concerted action on climate change. “Politics, the media, policy, human systems such as finance and governance, these were now the places where the blocks to climate action were to be found,” he said. The Centre’s mission was to understand how these societal arenas have responded to climate change, and how these responses could be strengthened.

Professor Derek Hand, Executive Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

Professor Derek Hand, Executive Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, noted the importance of the Centre for bringing diverse disciplines and perspectives together.

The recording of the opening remarks can be viewed here.

Harry Goddard, CEO of Deloitte Ireland

Harry Goddard, CEO of Deloitte Ireland, founding partner of the Centre, highlighted the role of corporations such as Deloitte in supporting other organisations through change, noting how hard change often is in practice. As an example, Goddard referenced Ireland’s smoking ban that was introduced against a backdrop of widespread smoking in public places. However, after all the measures there are still large numbers of smokers. “Kicking the habit is not easy. It is your role as business leaders, educators, and communicators to empower people to take action," he said. The recording of the address by Harry Goddard can be viewed here.

Panel 1 – How can the media respond to the climate crisis?

The recording of Panel 1 can be viewed here.

Dr Dawn Wheatley, DCU School of Communications

Dr. Dawn Wheatley of the DCU School of Communications and a former journalist, highlighted the challenge for correspondents in covering such a wide the range of topics. Dedicated climate and environmental correspondents develop expertise but the range of issues that need to be covered is large. In addition, "climate stories do not break they ooze" as in, climate impacts can be slow onset in ways that are hard to connect back to the issues of the day, leading to a potential clash with traditional news values. Wheatley questioned the idea that journalists can have a "view from nowhere" and that there is a need for the media to reorient how they think about "balance". Overall, there is a need for a more sophisticated understanding of objectivity coupled with a rigorous requirement for evidence.

Jon Williams, Managing Director, RTÉ News and Current Affairs

Jon Williams, Managing Director of RTÉ News and Current Affairs, stressed the role of media in providing both facts and context. Referring to criticism of RTE’s coverage of climate change last year, he acknowledged that much had been learned, "when we get it wrong, it's important that we say so." Reporting climate should now be "everyone's beat".

Orla Dwyer, Journalist, Journal.ie

Orla Dwyer, Climate Journalist with Journal.ie, noted how easily business-as-usual can be represented as uncontroversial in media. For example, a run of the mill segment about airport numbers recovering after Covid is an opportunity to question assumptions about growth and emissions, but rarely gets reported that way. A big challenge is to maintain the level of climate coverage when big things are happening elsewhere in the world. With the Covid-19 pandemic and the crisis in Ukraine it will be a challenge to keep climate reporting on the front page. This is one of the reasons why the Journal.ie set up a dedicated newsletter on climate change (Temperature Check).

Professor Pat Brereton, DCU School of Communications

Professor Pat Brereton of the DCU School of Communications looked at the role of art and the media in speaking to mass audiences. "Environmental communication typically speaks to the converted," he pointed out. But how do we speak to everyone else? Fictional narratives and storytelling are the best ways to communicate a message and can mobilise public opinion in ways that facts and statistics do not. He referenced the 2021 Adam McKay film Don't Look Up, which fancifully depicts moral bankruptcy and system collapse. Professor Brereton argued that we need creative imaginaries in climate communication in addition to reducing the carbon footprint of the film industry.

Professor Daire Keogh, President of DCU

Professor Daire Keogh, President of DCU, said that the creation of the DCU Centre for Climate and Society was “a recognition that climate change is no longer a problem for the physical sciences alone. It is a policy problem, it is a communications problem, it is a media problem, an ethics problem, an education problem, a corporate problem. In fact, it is a challenge that every area of society will have to respond to. With that in mind, the Centre’s research agenda will be critically important as we seek to be more effective in addressing key questions around climate change.” The recording of Professor Keogh's remarks can be viewed here.

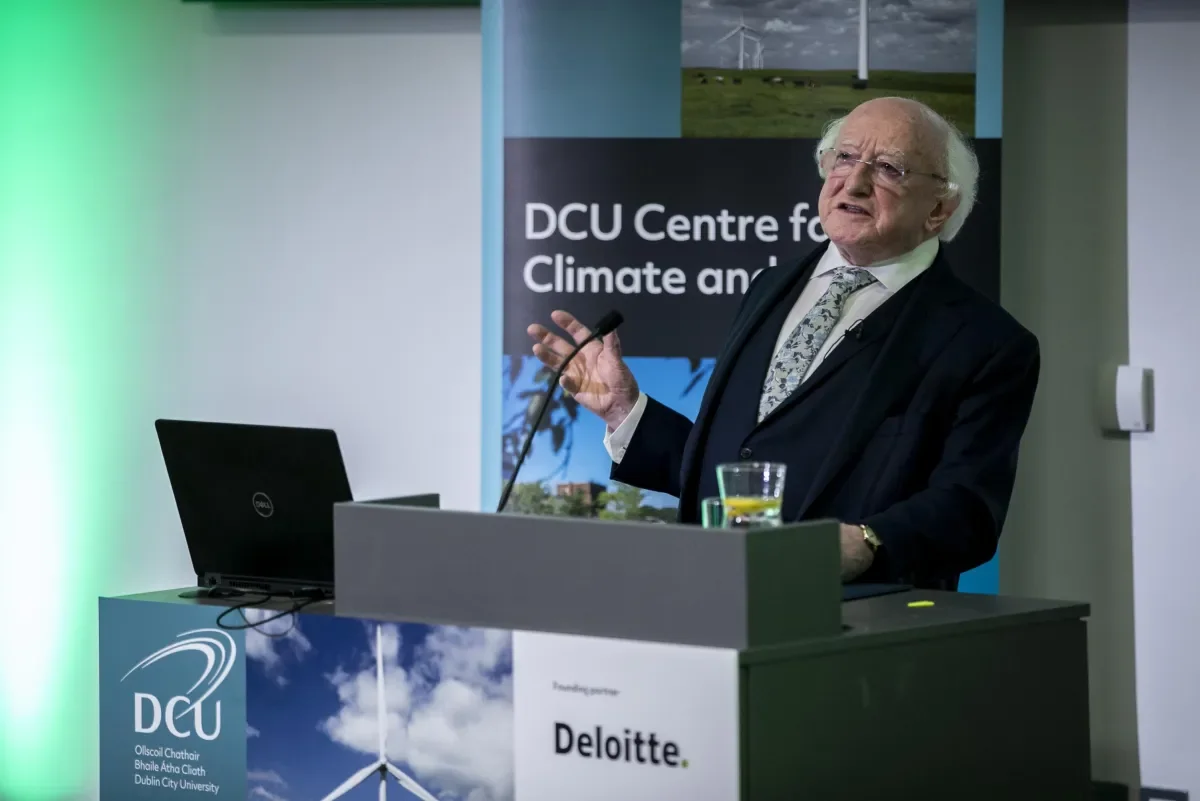

Keynote Address - President Michael D. Higgins

The recording of the keynote address by President Higgins can be viewed here.

President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, stressed the need for climate and the environment to become the unspoken, understood, taken-for-granted context for social discourse in the way that jobs and the economy are now. The Centre’s four pillars of research, education, engagement and journalism are areas that all require attention if we are to succeed in the climate challenge.

The President gave a wide-ranging address, connecting ecological responsibility with struggles for social justice, noting that uncritiqued individualism and modernisation is driven by a “myth of progress”.

He called for a return to anthropology as a means of understanding the climate crisis, and the inclusion of philosophy among the Centre’s multi-disciplinary approach.

The President also called for a greater role for the State in initiating climate action, suggesting that the State needed to reassert its authority after decades of “small government” discourses. The State had shown during the Covid-19 pandemic that it has wide social permission to take radical action.

President Higgins referenced the work of Zigmund Bauman and other social theorists of modernity and consumerism and noted the ways that modernity "consumes" the individual along the paths to "liquid modernity". The President warned that we are challenged to bring into being a world where, citing Tim Jackson, relationships and meaning take precedence over profits and power, where fulfilment is not driven by wealth accumulation.

Panel 2 – What does corporate climate leadership look like?

The recording of Panel 2 can be viewed here.

Dr. Aideen O Dochartaigh, DCU Business School

Dr. Aideen O Dochartaigh, of the DCU Business School argued that “merely setting targets is not leadership: achieving targets is leadership”. However, even early movers on climate tend to hold back on disclosing failure and this has an impact on transparency, which is essential for corporate climate leadership. For corporations, being transparent about both the impacts of the organisation and its supply chains on climate change can be difficult to measure at scale as there are so many different methodologies for measuring. For this reason, O Dochartaigh suggested that we need to think in terms of sectors not entities to ensure all scope 3 emissions are counted correctly. It's also important to report successes and failures. She noted that “environmental/ climate reports should be as transparent - and as boring - as financial accounts”.

Laura Wadding, Deloitte

Laura Wadding of Deloitte outlined the range of acronyms that represent the variety of rules that clients are expected to comply with, under mostly voluntary climate reporting methodologies. Many Irish companies have to comply with some or all of these rules simultaneously as they operate in more than one country. “This requires calibration of data, commitment, resources, and talent”, she said. In addition, because of the size of some of the international companies based here this is a significant commitment that puts Ireland in a potentially unique position. There is an increased demand for regulation and eventually disclosure will be mandatory, but information could be made available now.

Sarah Dempsey, AIB

Sarah Dempsey of AIB Ireland addressed the audience on the question of corporate climate leadership and outlined the actions that AIB has taken to put climate action at the core of its business model. She noted that a new CEO had come on board in recent years whose teenage daughters were putting him under pressure to respond to the school strike movement for climate. AIB has introduced new lending rules, and no longer supports fossil fuel investments. They have a range of ‘green’ financial products and aim to ultimately be a green bank with zero emissions from scope 1 and 2 by 2030.

Ali Sheridan, Corporate sustainability consultant

Ali Sheridan, corporate sustainability consultant and PhD candidate at Maynooth University then addressed the conference as a "recovering corporate sustainability advocate". Corporate climate action must be grounded in the scale and context of the climate crisis. But many Irish companies have rising emissions. “What do we accept as "enough" for corporate climate action”, she asked. While we have moved from strategies based on outright climate denial there is a risk now that corporations will present strategies that essentially mean climate delay e.g. using offset credits, or relying on techno-fixes. “We're conflating disclosure with action. We lack business models aligned with the science. Is industry getting strong enough signals? How will your industry exist on half of current emissions? Can your industry still exist? What will your customers/consumers be doing?”, she asked.

Panel 3 - Climate policy-making in a turbulent world

The recording of Panel 3 can be viewed here.

Jason Waskey, CEO of Blue Crab Strategies

Jason Waskey, CEO of Blue Crab Strategies, set up a consultancy that works with difficult, hard to abate sectors (for example, aviation, shipping and cement) and helped to establish the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance launched at COP26 in Glasgow. Waskey considered what the next five years of climate action would entail. It will be necessary to address blockages and ask whether they can be used as levers instead. Waskey gave five examples of potential blockages: Legal, financial, political, technological, and cultural.

Dr. Goran Dominioni, DCU School of Law and Government

Dr. Goran Dominioni of the DCU School of Law and Government suggested a novel proposal to address public opposition to carbon pricing: rebate some or all carbon revenues to the population by distributing them to frozen bank accounts or "antedated" cash transfers so that the funds are only released later but the public can see that the revenues have been returned.

Sharon Finegan, Director of the Environmental Protection Agency

Sharon Finegan, Director of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) noted that the Covid-19 pandemic was an "immediate" crisis, for which real-time data was available. Could real-time climate data help with decision-making? As with Covid, climate must consistently be to the fore of public consciousness for policy-makers to be under pressure to act. In her role in the Department of the Taoiseach, structural barriers, such as the absence of expertise on climate policy in the public sector, were identified.

Rose Wall, CEO of Community Law and Mediation

Rose Wall, CEO of Community Law and Mediation (CLM) spoke about the work of her organisation in connecting inequality and climate and the importance of accountability in climate policy-making. CLM hears stories regularly of fuel poverty, impacts from substandard accommodation and sanitation, and a lack of environmental enforcement. CLM is also starting to hear from households losing their homes due to coastal erosion and flooding, and also from communities concerned about the lack of green space. “This interconnection between inequality and climate is both a challenge and an opportunity for climate policy,” she said.

Director of Losing Alaska Tom Burke in conversation with Professor Pat Brereton

The final part of the conference was a discussion between Professor Pat Brereton and filmmaker Tom Burke of Broadstone Films on his film Losing Alaska, about residents of Newtok, Alaska are living on a fragile layer of melting permafrost and are essentially climate refugees. Tom Burke spoke about how it took three separate trips over 18 months to Alaska for the local communities to open up and tell their experiences. Pat Brereton remarked that the film is an example of what President Higgins recommended - taking an anthropological approach to documentary film-making that situates the immediate story in the context of the wider and deeper story of colonialism and resource extraction but without judgment or commentary.

The recording of the conversation can be viewed here.

Closing Remarks

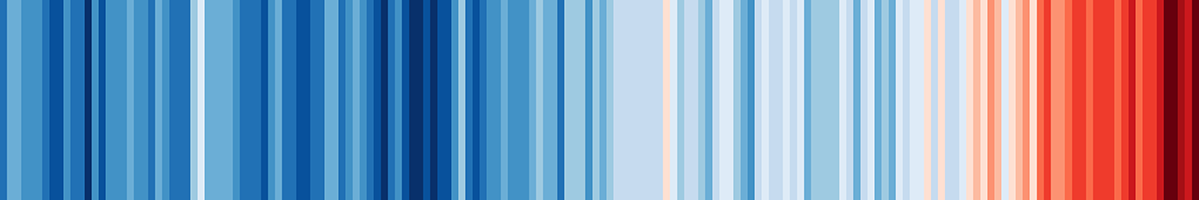

Dr. Diarmuid Torney, Co-Director of the Centre and Associate Professor at the School of Law and Government at DCU, said that the launch of the Centre is a milestone and chance to reflect on growth in research activity around climate change across disciplines at DCU. So many of the milestones relate to students who have undertaken the MSc in Climate Change. Dr Torney remarked that it was great to see all the work that students/graduates are doing in the climate field. “But the clock is ticking,” he said. “Since 2014, we've had the IPCC reports, climate strikes, a climate action plan, revision of the climate law in 2021 and the most recent assessment reports of the IPCC. Accountability, the importance of communications and climate justice came through as an issue in all the panel discussions during the conference. We hope the Centre will provide the space for those challenging conversations to encourage each other to go further.” The recording of the closing remarks can be viewed here.