The European Parliament election and its consequences

Prof Federico Fabbrini

On 6-9 June 2024 European citizens will elect the European Parliament (EP). This is the 10th election of the EP since the introduction of direct universal suffrage in 1979 (the older composition of the EP was made up of delegates from the national Parliaments) – and the 1st one without the United Kingdom as a member state (Brexit having occurred in 2020).

The EP elections are very important, but they have different consequences than national elections. In parliamentary democracies – like Ireland, or Italy – citizens vote for the national Parliament, and on the basis of the electoral results a government (possibly based on a coalition) is formed, with its own political majority, led by a prime minister. The European Union (EU), however has a more complex system of government than its member states. This is an inevitable consequence of the fact that the EU is a polity that brings together 27 countries. In the EU governance system the EP is only one of several institutions that take political decisions: the EP works alongside the European Council (the body representing Heads of State and Government of the 27 member states), by the Council (the body representing the ministers of the 27 member states, who meet in different compositions depending on the topics – for instance finance, or foreign affairs, or agriculture), and by the European Commission (which has the task to administer the EU and promote the European general interest, including through a monopoly of the EU legislative initiative).

According to the European Treaties, as modified by the Treaty of Lisbon of 2007, the European Commission has a term of office of 5 years, is nominated by the European Council taking into account the results of the EP, and is appointed only after a vote of confidence by a majority of the EP. In 2014 the main European political parties represented in the EP decided to put forward lead candidates (Spitzenkandidaten, in German) for the European elections, clarifying that they would support as President of the European Commission only the candidate from the party list which had received the largest share of the popular votes by European citizens. This bet paid off and in 2014 the European Council appointed Jean-Claude Juncker – the lead candidate of the centre-right European Peoples’ Party (EPP) – as President of the Commission. In 2019, however, the EP’s attempt to impose its lead candidates did not work, and as a result the European Council autonomously chose the next President of the European Commission. The latter, as is well known, was Ursula von der Leyen, who at the time was Minister of Defense in Germany and was not running for European elections.

This year there are several uncertainties regarding the institutional dynamics that will prevail in the appointment of the future leadership of the Commission, in light of the EP elections. On the one hand, the current President von der Leyen is running for a second mandate, and has been nominated as the lead candidate for the EPP, which favors her as incumbent. On the other hand, the European Council could be interested in reasserting its prerogatives and autonomously choose the President of the Commission. In this context, however, it is clear that the results of the EP elections will have a particular weight. Since the candidate proposed by the European Council as President-elect of the Commission still needs to obtain a vote of confidence by an absolute majority of the EP, the 6-9 June elections will have an unusual importance. In fact, the success of pro-European political forces, or alternatively the rise of Eurosceptic factions, will directly influence the choices that the European Council will make, and thus the outlook of the new European Commission.

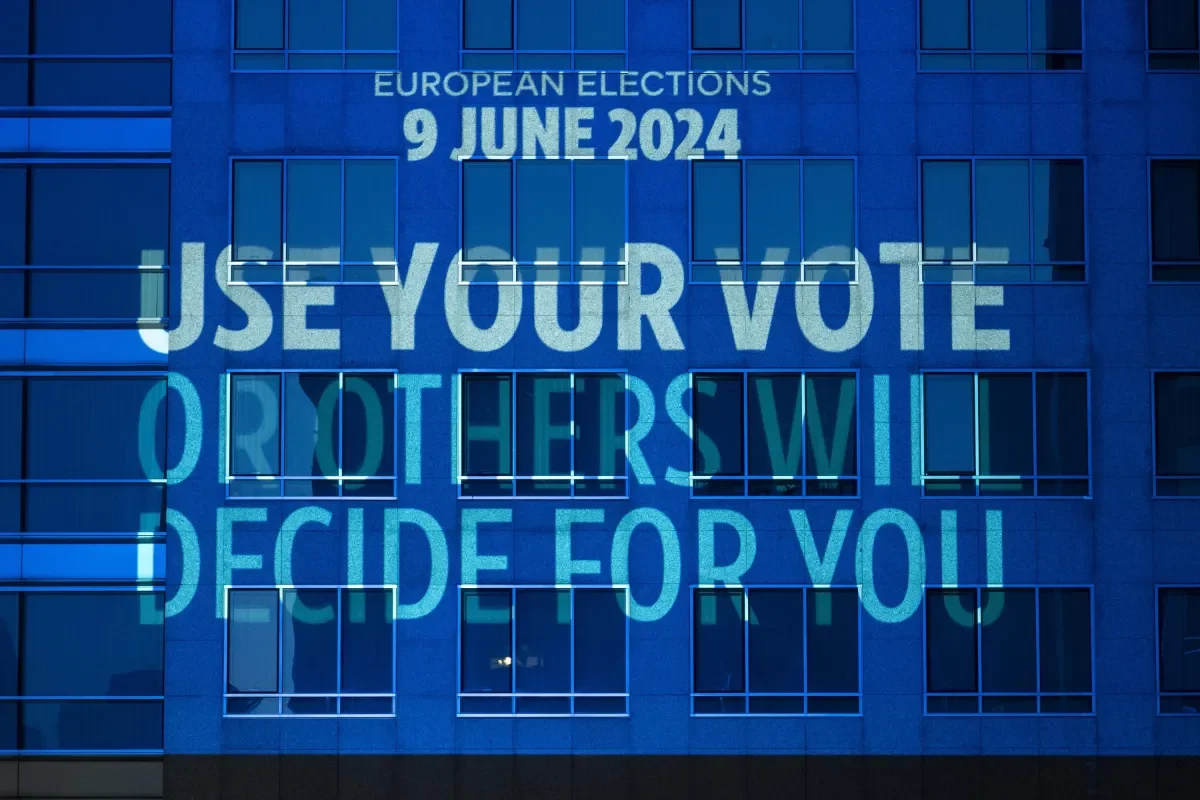

Even if the EU does not have a parliamentary system of government, therefore, it is important that European citizens exercise their rights and go to vote for the elections of the EP – the second largest democratic exercise in the world (after India’s). At a time when liberal democracy is under threat around the globe, we should be mindful of the electoral privileges we enjoy in this part of the European continent, and thus use our vote for the EP – the most democratic institution of our united Europe.

Federico Fabbrini is Full Professor of EU Law, and Founding Director of the Brexit Institute and the Dublin European Law Institute (DELI) at Dublin City University.